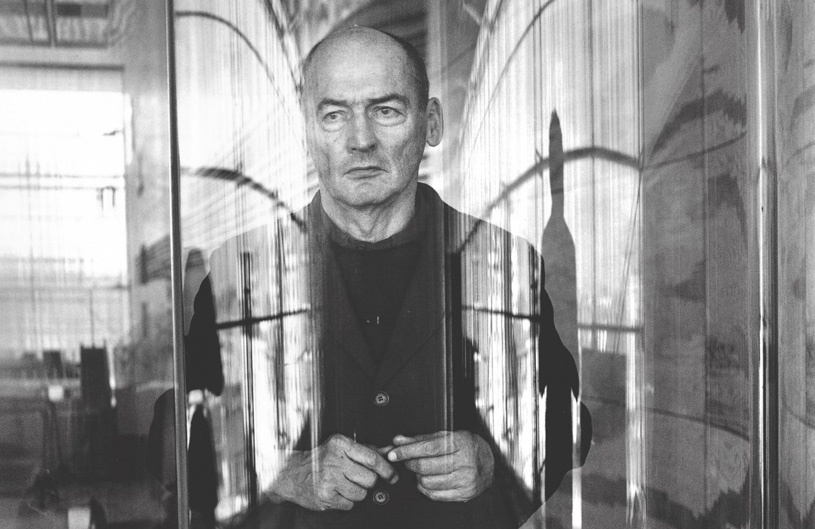

Интервью Рема Колхаса журналу «Spiegel» 2011

12/16/2011

Interview with Star Architect Rem Koolhaas

Part 1: We're Building Assembly-Line Cities and Buildings

SPIEGEL: Welcome, Mr. Koolhaas. So, this is SPIEGEL's new building, and we are standing here in its atrium.

Rem Koolhaas: Why are you whispering like that?

SPIEGEL: We are? We hadn't noticed.

Koolhaas: I know. The acoustics in this atrium signaled to you that it'd be better to whisper.

SPIEGEL: What makes you say that?

Koolhaas: The acoustics swallow the sound. The silence intimidates you. Do you feel comfortable here?

SPIEGEL: It's taking some people a bit of time to get used to it.

Koolhaas: That could have something to do with the fact that this is a very ambitious building. Look, we -- that is, my firm and I -- work in a completely non-descript building in Rotterdam. It couldn't be plainer. It's from the 1960s, and it's an open room with a nice view. We are almost ecstatically happy. Why? We can do anything there. We can imprint our personality onto the building. In an ambitious building like yours, it might be the other way around.

SPIEGEL: One has the feeling that the building is more powerful than those working inside it.

Koolhaas: Well, you've only been here a few months. You're going through an initial learning process. Over time, you'll probably learn to understand your building. And the building will also learn to understand you.

SPIEGEL: That sounds a bit esoteric.

Koolhaas: But it's true. Our building in Rotterdam has less character than yours. In fact, it has zero character. It can be wonderful when a building has character, but it can also be an obstacle. It can limit you. I have mixed feelings about this.

SPIEGEL: Just now, when we were in HafenCity, standing in the new Unilever headquarters building designed by the Behnisch architecture firm, you said that ugliness can make a building more open.

Koolhaas: I don't think the Unilever headquarters is ugly. But the building is more disorganized and more chaotic. And disorder can have a stimulating effect. It is more accessible to people than a rigid form. What's more, it was louder there. But, with time, you'll get louder here. You seem a little unhappy with this building that was built for you. And you are skeptical about this new neighborhood in which the building is located. I get the feeling that what you need from me isn't so much an interview as an hour of therapy.

SPIEGEL: Isn't skepticism appropriate?

Koolhaas: Perhaps. But I can't comfort you. Nowadays, and everywhere, we are in a situation in which many things are interacting and producing results like this building or this HafenCity. It doesn't matter whether it's in Hamburg, Dubai or China. It would be easy to say: "The architect has failed" or "The city has failed" or "The evil consortium of investors is to blame." No, it's the interplay of all these conditions that produces soulless buildings.

SPIEGEL: What kinds of conditions?

Koolhaas: These days, when a building is constructed, there is less individual involvement. Take the old SPIEGEL building by Werner Kallmorgen. One can assume that (SPIEGEL founder) Rudolf Augstein saw this building as his personal statement. There was something at stake for him when he had it built. It was supposed to reflect the identity of the magazine. But, nowadays, a client is in a much more abstract and opaque situation. Money has become more important; a lot more people are involved. Nowadays, a building like this is mainly a development project. Take this building, for example: Its neighbor is its double. SPIEGEL (the German word for "mirror") is mirroring itself. Of course, that introduces a personality crisis. And there always has to be an atrium! In its emptiness, it forms the actual substance of the generic city.

SPIEGEL: Soulless buildings in generic cities? That isn't exactly comforting.

Koolhaas: Soulless means that it's difficult to determine what a building wants to convey. It is difficult to pinpoint the elements that make the difference. In my essay "The Generic City," I tried to get to the bottom of this soullessness, though in terms of entire cities rather than buildings. These days, we're building assembly-line cities and assembly-line buildings, standardized buildings and cities.

SPIEGEL: We just toured HafenCity. Is it one of these typical generic cities?

Koolhaas: Yes. (It has) this strange sense of familiarity, as if you've been there before. And yet you haven't. It's all the familiar building blocks that are constantly being assembled in different ways. If you look down the main thoroughfare of HafenCity from your building, you'll see that this street tells the entire history of architecture over the last decade: no clear ambitions.

SPIEGEL: Have we yielded control over our cities?

Koolhaas: There is still a degree of residual control -- in other words, the attempt to create a unity by having the same heights, the same materials and a similar structural vocabulary. These are meant to be statements of respect. And, although only established architects were approved here, despite all the effort, the results are disappointing. And it's the same everywhere.

Part 2: Architecture as the 'Cherry on the Cake'

SPIEGEL: In "The Generic City," you ask whether it might not be intentional that our cities are becoming increasingly similar and faceless.

Koolhaas: Yes. And the answer could be: The traditional city is very much occupied by rules and codes of behavior. But the generic city is free of established patterns and expectations. These are cities that make no demands and, consequently, create freedom. Some 80 percent of the population of a city like Dubai consists of immigrants, while in Amsterdam it is 40 percent. I believe that it's easier for these demographic groups to walk through Dubai, Singapore or HafenCity than through beautiful medieval city centers. For these people, (the latter) exude nothing but exclusion and rejection. In an age of mass immigration, a mass similarity of cities might just be inevitable. These cities function like airports in which the same shops are always in the same places. Everything is defined by function, and nothing by history. This can also be liberating.

SPIEGEL: The German philosopher and media theorist Peter Sloterdijk has described your essay "The Generic City" as the "zero hour of architectural history." How did you hit upon the idea of describing interchangeability as a deliberate development?

Koolhaas: Because all we do is complain. You are too, by asking why everything here looks so interchangeable. Well, perhaps it's because there are people who like it this way. I have always created portraits of individual cities. "Delirious New York" was my first essay.

SPIEGEL: It brought you overnight fame as an architectural theoretician. That was in 1978, before you had even made a name for yourself as an architect.

Koolhaas: I went on to analyze cities like Atlanta, Singapore and Lagos. I have always been interested in very special and unique cities. But it suddenly occurred to me that the differences between these cities actually aren't all that interesting. I wanted to uncover their similarities. The essay "The Generic City" was meant to be applicable to any city.

SPIEGEL: One could also describe the face of our cities as the face of neoliberalism.

Koolhaas: Under neoliberalism, architecture lost its role as the decisive and fundamental articulation of a society.

SPIEGEL: How does a society articulate itself?

Koolhaas: Take, for example, the prefabricated building. No matter how misguided this ultimately turned out to be, it actually was a very clear articulation. But neoliberalism has turned architecture into a "cherry on the cake" affair. The Elbphilharmonie is a perfect example: It's icing on the cake. I'm not saying that neoliberalism has destroyed architecture. But it has assigned it a new role and limited its range.

SPIEGEL: In the last few years, more and more cities have sold land to international investors. At the same time, these investors have looked at architecture from a purely economic perspective rather than from an urban-planning one.

Koolhaas: It's a bit more complicated than that. During this period, the political system has tried to maintain the appearance of control by setting many rules: what height restrictions have to be adhered to, which materials have to be used, what artistic language the façades should speak. This has merely concealed the fact that so much control over use had been ceded to the investors. The commercial impulse, paired with bureaucratic rules, leads to these highly unsatisfactory results: You have neither the structures of an unfettered economic drive, which make New York and London so exciting, nor the clear planning of German cities from the Gründerzeit period (ed's note: generally speaking, in the second half of the 19th century).

SPIEGEL: Do you want to see a return to greater government control? This longing shines through in your massive new book about the Metabolists, a Japanese group of architects that is largely unknown in the West.

Koolhaas: That's right. The state wasn't always the hopeless and powerless entity it is often perceived to be in the West today. We learn this from the Metabolists, who the government engaged in 1960 to combat their country's structural weaknesses: earthquakes, tsunamis, the parceling of the country. Another interesting thing about the Metabolist movement is the fact that, despite being great individualists, its members acted as a group. Today, this possibility no longer exists. The compulsion to compete has isolated architects.

SPIEGEL: Astonishing. But haven't you also benefited from the system of "star architects" who dominate the major international architecture projects these days?

Koolhaas: It's true that we architects are getting a lot more attention today. But we are being taken less seriously. Perhaps this is the therapeutic moment of our conversation, after all: I refuse to admit to a crisis. Is HafenCity truly the expression of a crisis? It might be that only the upper 10 percent live there, and one could criticize that. But at least we should take notice of the fact that these upper 10 percent are completely happy with this type of architecture.

SPIEGEL: Is a star architect like you even interested in whether people who live or work in your buildings are complaining? How is it with your building for the Chinese state television network CCTV in Beijing?

Koolhaas: I take this very seriously. I still go to Beijing once a month. Even in China, the building's users are involved in the process. We listen to them and their suggestions. This is a very democratic process, even there.

SPIEGEL: Ten years ago, you had to decide whether to participate in the competition for the new development of the Ground Zero site or to apply for the construction of the CCTV tower. You chose China. Is it easier to build there than in the Western democracies?

Koolhaas: It's never easy to build. It's just as difficult to convince the Chinese as it is to convince Americans or Germans. The only difference is that the people making the decisions in China are in their mid-30s. In the United States, they're in their mid-70s.

SPIEGEL: So, are you saying that an authoritarian country is offering architecture new possibilities?

Koolhaas: You'll never get me to sign off on that. I'm not pessimistic when it comes to the prospects for the West, for democratic societies, and the ability to build strong statements here. The only reason I chose not to take part in the Ground Zero competition was that the project's connection to the past was too clear for my taste. There is more willingness to experiment in China. So much is being built there -- entire cities! -- that greater risks have to be taken. There, failure is not a disaster.

Part 3: The Perils of Working in 'an Unstable Ideological Environment'

SPIEGEL: Is it true that only 5 percent of your designs are actually built?

Koolhaas: Yes.

SPIEGEL: That must be frustrating.

Koolhaas: That's our dirty secret. We architects are celebrated as heroes -- but humiliation is part of our daily lives. The biggest part of our work for competitions and bid invitations disappears automatically. No other profession would accept such conditions. But you can't look at these designs as waste. They're ideas; they will survive in books.

SPIEGEL: A few years ago, you unveiled a spectacular design for a science museum here in HafenCity, the so-called Science Center. It still hasn't been built.

Koolhaas: I haven't heard anything about it in a long time.

SPIEGEL: How long did you work on the design?

Koolhaas: Maybe three years.

SPIEGEL: And then?

Koolhaas: Then, we suddenly stopped hearing anything. We couldn't reach anybody anymore. The last thing we heard was that a young woman was trying to turn our design for a museum into a residential building.

SPIEGEL: Is that sort of thing normal?

Koolhaas: Very typical. You get to a point where you have nothing to say to each other anymore. The funding is frozen, the project is in a holding pattern, and both sides gradually lose interest.

SPIEGEL: Do you have a telephone number you can call?

Koolhaas: Yes, but the city official in charge of the project has already been replaced twice. I don't think anyone there knows us anymore.

SPIEGEL: While roughly 14 percent of the office space in HafenCity is empty, there is demand for more apartments. What causes this kind of faulty planning?

Koolhaas: Let me tell you a story. In 1980, I received an offer to build low-income housing in an industrial area in Amsterdam. The idea was to realize the social-democratic dream of modern apartments: generous buildings, and no compartmentalized commercial use. Five years later, in precisely the same year in which the buildings were completed, a delegation of the same social-democratic party that had hired us went to Baltimore. The city was in the process of gentrifying its harbor district. Apartments were built for the middle and upper classes, and fashionable shops were opened, a little like it is here in Hamburg. When the Social Democrats returned, they were no longer interested in our low-income housing. They suddenly felt that this austere, socialist architecture was horrible.

SPIEGEL: So, what does that mean?

Koolhaas: As an architect, one operates in an unstable ideological environment. What is true today can be completely wrong in five years, and in 25 years it's most certainly wrong. Ridiculous.

SPIEGEL: Does the criticism bother you? One could attack you for having built a symbol of power for a dictatorship like China.

Koolhaas: I have taken all criticism in that context seriously. My answer has always been that what happens to China affects us, as well. That's why it's important for us to be involved there. I have certain hopes for China, but I'm also aware of the risk that the country could move in a completely different direction.

SPIEGEL: Isn't it odd for this new, self-confident China to commission a Western architect?

Koolhaas: When I received the commission in 2002, a window was open for a brief time. I don't believe that they would still award the commission to a Western architect today.

SPIEGEL: Are you sad you didn't receive the commission for the SPIEGEL building?

Koolhaas: You know, you can design and build a lot as an architect, but there is only a handful of buildings that you absolutely want to do -- because you have the feeling that they are directly relevant to your own life. I was once a journalist with a weekly magazine, and I remain an admirer of SPIEGEL to this day.

SPIEGEL: But?

Koolhaas: We repeatedly made it clear that we were interested. Then we met with the person in charge of the bidding process because we wanted a direct commission.

SPIEGEL: You didn't want to participate in the competition?

Koolhaas: No. We believe that direct commissions lead to better buildings. In competitions, you're compelled to make compromises.

SPIEGEL: Do you or don't you like our building?

Koolhaas: You'll get used to it. But I believe you have to conquer the lobby. Buy two rugs, sew the two rugs together, then buy a third one and declare the lobby occupied. Occupy SPIEGEL!

SPIEGEL: Mr. Koolhaas, thank you for this interview.

Interview conducted by Philipp Oehmke and Tobias Rapp; translated from the German by Christopher Sultan

Источник: www.spiegel.de